Dynamical friction

Dynamical friction is a term in astrophysics related to loss of momentum and kinetic energy of moving bodies through a gravitational interaction with surrounding matter in space. It is sometimes referred to as gravitational drag, and was first discussed in detail by Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar in 1943.[1][2][3]

Contents |

Intuitive account

An intuition for the effect can be obtained by thinking of a massive object moving through a cloud of smaller lighter bodies. The effect of gravity causes the light bodies to accelerate and gain momentum and kinetic energy (see slingshot effect). By conservation of energy and momentum, we may conclude that the heavier body will be slowed by an amount to compensate. Since there is a loss of momentum and kinetic energy for the body under consideration, the effect is called dynamical friction.

Another equivalent way of thinking about this process is that the light bodies are attracted by gravity toward the larger body moving through the cloud, and therefore the density at that location increases and is referred to as a gravitational wake. In the meantime, object under consideration has moved forward. Therefore, the gravitational attraction of the wake pulls it backward and slows it down.

Of course, the mechanism works the same for all masses of interacting bodies and for any relative velocities between them. However, while the most probable outcome for an object moving through a cloud is a loss of momentum and energy, as described intuitively above, in the general case it might be either loss or gain. When the body under consideration is gaining momentum and energy the same physical mechanism is called slingshot effect, or gravity assist. This technique is sometimes used by interplanetary probes to obtain a boost in velocity by passing close by a planet.

Chandrasekhar dynamical friction formula

The full Chandrasekhar dynamical friction formula for the change in velocity of the object involves integrating over the phase space density of the field of matter and is far from transparent.

A commonly used special case is where there is a uniform density in the field of matter, with matter particles significantly lighter than the major particle under consideration and with a Maxwellian distribution for the velocity of matter particles. In this case, the dynamical friction force is as follows:[4]

![\textbf{f}_{dyn} = M \frac{d\textbf{v}_M}{dt} = -\frac{4\pi \mbox{Ln}(\Lambda) G^2 M^2 \rho}{v_M^3}\left[\mbox{erf}(X)-\frac{2X}{\sqrt{\pi}}e^{-X^2}\right]\textbf{v}_M](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/9fca9864fc73efba00fd9ec78b602715.png)

where

- G is the gravitational constant.

- M is the mass under consideration.

is the velocity of the object under consideration, in a frame where the center of gravity of the matter field is initially at rest.

is the velocity of the object under consideration, in a frame where the center of gravity of the matter field is initially at rest. is the ratio of the velocity of the object under consideration to the modal velocity of the Maxwellian distribution. (

is the ratio of the velocity of the object under consideration to the modal velocity of the Maxwellian distribution. ( is the velocity dispersion).

is the velocity dispersion). is the "error function" obtained by integrating the normal distribution.

is the "error function" obtained by integrating the normal distribution. is the density of the matter field.

is the density of the matter field. is the "Coulomb logarithm".

is the "Coulomb logarithm".

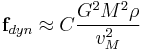

In general, a simplified equation for the force from dynamical friction  has the form

has the form

where the dimensionless numerical factor  depends on how

depends on how  compares to the velocity dispersion of the surrounding matter.[5]

compares to the velocity dispersion of the surrounding matter.[5]

Density of the surrounding medium

The greater the density of the surrounding medium, the stronger the force from dynamical friction. Similarly, the force is proportional to the square of the mass of the object. One of these terms is from the gravitational force between the object and the wake. The second term is because the more massive the object, the more matter will be pulled into the wake. The force is also proportional to the inverse square of the velocity. This means the fractional rate of energy loss drops rapidly at high velocities. Dynamical friction is, therefore, unimportant for objects that move relativistically, such as photons. This can be rationalized by realizing that the faster the object moves though the media, the less time there is for a wake to build up behind it.

Applications

Dynamical friction is particularly important in the formation of planetary systems and interactions between galaxies.

Protoplanets

During the formation of planetary systems, dynamical friction between the protoplanet and the protoplanetary disk causes energy to be transferred from the protoplanet to the disk. This results in the inward migration of the protoplanet.

Galaxies

When galaxies interact through collisions, dynamical friction between stars causes matter to sink toward the center of the galaxy and for the orbits of stars to be randomized. This process is called violent relaxation and can change two spiral galaxies into one larger elliptical galaxy.

Galaxy Clusters

The effect of dynamical friction explains why the brightest (more massive) galaxy is found at the center of a galaxy cluster. The effect of the two body collisions slows down the galaxy, and the drag effect is greater the larger the galaxy mass. When the galaxy loses kinetic energy, it moves towards the center of the cluster. However the observed velocity dispersion of galaxies within a galaxy cluster does not depend on the mass of the galaxies. The explanation is that a galaxy cluster relaxes by violent relaxation, which sets the velocity dispersion to a value independent of the galaxy's mass.

Photons

Fritz Zwicky proposed in 1929 that a gravitational drag effect on photons could be used to explain cosmological redshift as a form of tired light.[6] However, his analysis had a mathematical error, and his approximation to the magnitude of the effect should actually have been zero, as pointed out in the same year by Arthur Stanley Eddington. Zwicky promptly acknowledged the correction,[7] although he continued to hope that a full treatment would be able to show the effect.

It is now known that the effect of dynamical friction on photons or other particles moving at relativistic speeds is negligible, since the magnitude of the drag is inversely proportional to the square of velocity. Cosmological redshift is conventionally understood to be a consequence of the metric expansion of space.

Notes and references

- ^ Chandrasekhar, S. (1943), "Dynamical Friction. I. General Considerations: the Coefficient of Dynamical Friction", Astrophysical Journal 97: 255–262, Bibcode 1943ApJ....97..255C, doi:10.1086/144517

- ^ Chandrasekhar, S. (1943), "Dynamical Friction. II. The Rate of Escape of Stars from Clusters and the Evidence for the Operation of Dynamical Friction", Astrophysical Journal 97: 263–273, Bibcode 1943ApJ....97..263C, doi:10.1086/144518

- ^ Chandrasekhar, S. (1943), "Dynamical Friction. III. a More Exact Theory of the Rate of Escape of Stars from Clusters", Astrophysical Journal 98: 54–60, Bibcode 1943ApJ....98...54C, doi:10.1086/144544

- ^ Binney, James; Scott Tremaine (1994), Galactic Dynamics, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08445-9

- ^ Carroll, Bradley; Dale Ostlie (1996), An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics, Weber State University, ISBN 0-201-54730-9

- ^ Zwicky, F. (10 1929), "ON THE REDSHIFT OF SPECTRAL LINES THROUGH INTERSTELLAR SPACE", Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 15 (10): 773–779, Bibcode 1929PNAS...15..773Z, doi:10.1073/pnas.15.10.773, PMC 522555, PMID 16577237, http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=522555.

- ^ Zwicky, F. (1929), "On the Possibilities of a Gravitational Drag of Light", Physical Review 34 (12): 1623–1624, Bibcode 1929PhRv...34.1623Z, doi:10.1103/PhysRev.34.1623.2.